Noncompete advocates nationwide have been dealt a blow by the culmination of a six-year Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigation on the propriety and enforceability of noncompete agreements in the employer-employee context. In an explosive 570 page memorandum, the FTC has issued a “Final Rule” addressing the future – or, more accurately, the lack of future – of noncompetes in the United States. Read on to see how the FTC noncompete ban affects you, and how to protect yourself or your business going forward . . .

What does the new FTC noncompete ban rule do?

Bans all Noncompete Agreements Nationwide Going Forward

The gist of the newly created subchapter J to the previously existing Chapter I, Title 16 of the Code of Federal Regulations addresses “Rules Concerning Unfair Methods of Competition.” In a turn of events rarely considered outside the context of legal scholarship, the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) has deemed that noncompete agreements constitute restraints on trade, which in turn violate antitrust provisions previously existing in U.S. law.

On this basis, 16 § 910.2(a) now provides that 120 days following the publishing of the “Final Rule” in the Federal Register, it will be an unfair method of competition for a business or individual (i) to enter into or attempt to enter into a non-compete clause; (ii) to enforce or attempt to enforce a non-compete clause; or (iii) to represent that a worker or senior executive is subject to a non-compete clause. 16 § 910.2(a)(1). Workers, in this context, means any person who “worked” – whether paid or unpaid (thus including volunteers), “without regard” to titles, status under the law, or designation as an employee, contractor, intern, or sole proprietor. 16 § 910.1.

Translated, employers will no longer be able to offer or demand that workers – regardless of experience or “executive status” – enter into noncompete agreements. If you’re not sure whether the person you seek to bind is actually a worker, odds are they meet the definition if they perform any sort of service on the employer’s behalf.

Retroactively Bans All Noncompete Agreements for Non-Senior Executives

In a decidedly pro-labor move, the newly-promulgated FTC noncompete ban retroactively applies to noncompete agreements entered into between employers and “non-senior executives.” 16 § 910.1 provides that a senior executive means a worker who (1) was in a policy-making position, and (2) received total annual compensation (including salary, commissions, bonuses, or other nondiscretionary compensation; excluding board/lodging, medical insurance, retirement plan contributions, or other similar fringe benefits) of at least $151,164 in the year prior to the worker departing from employment.

Therefore, if an employee makes less than $151,164 per year, even if they have previously entered into a valid noncompete agreement prior to the issuance of this Final Rule, the noncompete to which they have agreed is now rendered void and unenforceable by government regulation. If an employee makes more than $151,164, it is a fact based inquiry on whether the employee is an officer of the employer’s business entity with “policy-making authority,” which is a broad term encompassing, but not limited to, officers or other persons who can exercise or exert influence over policy decisions. While presidents and chief executive officers are presumed to have policy-making authority, any individual who makes decisions that “have a significant impact on the business” will likely be considered senior executives. Partners in a business – such as physician partners in a small practice – also generally qualify as senior executives, but the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule stresses that noncompetes which go to a partner’s ability to sell their membership interest in a venture and thereafter compete with the venture are likely exempt under the § 910.3 sale of business exception (see below for further details).

Allows For Previously Negotiated Senior Executive Noncompete agreements

Proceeding on the assumption that senior executive, or “C-Suite” individuals likely possess the business acumen or bargaining power to negotiate their own employment contracts, the Final Rule contains a carve-out for noncompete agreements entered into between employers and senior executives before the Final Rule goes into effect. Therefore, while senior executives can no longer be bound to non-compete agreements after the Final Rule’s effective date, any noncompete agreements they have previously entered into will remain enforceable so long as they do not contravene previously-existing law.

Thus, to predict the likely outcome under Texas law, if an executive is currently bound to a noncompete agreement and violates its terms in the coming year, the FTC’s Final Rule will likely not operate as an automatic bar to the employer’s right to sue the executive for a breach of the noncompete – but the parties will still be required to litigate whether the actual time/scope/geographic area of the noncompete agreement is reasonable in light of the employer’s business.

Requires Notice to Workers with Noncompete Agreements

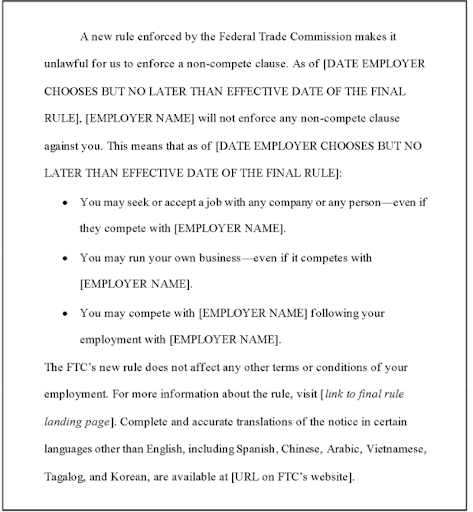

16 § 910.2(b) requires that, to the extent an employer has an existing non-compete clause that doesn’t meet an applicable exception (such as a preexisting senior executive agreement or a sale of business transaction agreement), employers are mandated to provide clear and conspicuous notice to the worker by the effective date that the worker’s non-compete clause will not be, and cannot legally be, enforced against the worker.

The notice must (1) identify the employer; (2) be delivered to the worker, either in physical written format or via email, or via text message. Insofar as an employer does not have a record of a street address, email address, or phone number, the employer is excused from notifying the worker. Finally, 16 § 910.2(b) provides a “model language” notice, an image of which is included below:

Does Not Affect Noncompete Agreements in Sale of Business Transactions or Ongoing Lawsuits

As the subsection states, the Final Rule only applies to noncompete agreements in the employer-employee context. Merger/Aquisition transactions, business buyouts, or franchisor-franchisee relationships remain unaffected by the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule. 16 § 910.3(a). Thus, it is still permissible to negotiate a “promise not to compete” from an individual engaging in a bona fide sale of a business entity, a sale of their business interest, or a sale of all or substantially all of a business’s assets. Note that such promises not to compete must be carefully made contingent on the sale of the business to remain enforceable – it is unlikely that employer-employee noncompete agreements masquerading as business entity sales agreements will be enforced.

Further, to the likely bitter disappointment of all those employees currently litigating (or who will be litigating within the next four months) noncompete disputes, the Final Rule does not apply to lawsuits brought to enforce the non-compete prior to the effective date. 16 § 910.3(b).

Preemption of Conflicting State Noncompete Laws

Finally, likely setting up a Supreme Court showdown, the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule seeks to preempt state law concerning noncompete agreements to the extent state law conflicts with the Rule. Thus, although Texas Bus. & Com. Code § 15.50 permits noncompete agreements if they (1) are ancillary to or part of an otherwise enforceable agreement, (2) to the extent that they contain reasonable limitations as to time, geographical area, and scope of activity that (3) do not impose a greater restraint than is necessary to protect the goodwill or other business interest of the promisee, the fact that Texas law allows for noncompete agreements at all means that the Final Rule will preempt – i.e. negate – Texas law.

Do I have a Noncompete Agreement?

At this point, the first question you’ll need to ask (whether you are an employee or an employer) is whether you are dealing with a noncompete agreement. This is a key inquiry, and we predict that going forward (if the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule withstands the impending legal challenges it doubtlessly will face), one of the major shifts we’ll perceive in the employment field is the artful drafting of similar restrictive covenants – such as Nondisclosure Agreements, Confidentiality Clauses, or Trade Secret Restrictions – to push boundaries on how far a restrictive covenant can go before it becomes a noncompete agreement.

Per the Final Rule, a non-compete clause means a term or condition of employment that prohibits, penalizes, or prevents a worker from (i) seeking or accepting work in the United States with a different person where such work would begin after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition; or (ii) operating a business in the United States after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition. 16 § 910.1.

For the layperson, the distinction you need to focus on is what the worker is prohibited from doing. If your employee is prohibited from using certain information, applying special formulas, or soliciting certain clients, then the specific nature of these restrictions likely implicates an NDA, Confidentiality Clause, or the like, and remains enforceable. If, however, the employee is simply prohibited from working in a field attenuated to their current area of employment – even if the prohibition is based on a desire to protect confidential information – then the agreement is likely a noncompete which will be prohibited under the Final Rule.

Further questions regarding whether a certain agreement constitutes a non-compete or some other form of restrictive covenant should be properly addressed to an attorney for your ease of mind.

As an Employee, What are my Rights?

If you or someone you know is currently subject to a noncompete agreement they wish to escape from, my suggestion to you is to set your watch and begin counting down the days until the effective date the Final Rule goes into effect (remember, 120 days after it is published in the Federal Register). DO NOT, UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCE, take the passage of this Final Rule to mean you can quit your job tomorrow and not be bound by the agreement – remember, the Final Rule does not apply to ongoing lawsuits, which means that if you quit tomorrow, breach the agreement by landing a new job next week, and are sued by your former employer the week after, you will still have to defend yourself in a lawsuit if your former employer files it before the effective date.

Further, while this is a significant victory for pro-labor advocates (and employees generally), we wouldn’t suggest getting too excited, as the constitutionality of this statute is likely to be challenged by some very powerful business interests, and the Final Rule is unlikely to stay in effect for the reasons we discuss below. However, during the brief period of time in which the Final Rule is in effect and no ruling on its constitutionality has been issued, you as an employee will possess agency to quit, breach your noncompete, and inform your former employer that any attempt to enforce the noncompete will be likely to fail so they may as well not try.

Finally, there is no language in the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule about the return of any compensation or consideration you may have received in exchange for signing a noncompete. Often, businesses will attempt to “sweeten the deal” by offering financial bonuses or incentives to coerce employees into signing noncompete agreements. If you have already received such an incentive, you are unlikely to have to return the money. However, if you enter into a noncompete going forward, knowing that it is (for the foreseeable future) void and unenforceable, and receive compensation for doing so, your employer can likely attempt to sue you for a return of the compensation.

As an Employer, What Should I do Going Forward?

As an employer, your first order of business will be to compile a list of all current and former employees who are currently subject to an active noncompete agreement. Of those employees, if any are actively violating their noncompete, you have a period of approximately four months to bring suit against them before the Final Rule interferes. Concurrently, before the expiration of the four-month period, you have a duty to provide the notice discussed above to every employee who is subject to an active noncompete agreement.

Further, as a matter of sound business strategy, if you possess any senior executives who are not currently bound to a noncompete, you may wish to bind them before the four-month effective date runs. Additionally, we highly recommend you review your business operations to highlight valuable assets and essential confidential information – and the people who have access to such information. Remember, NDAs and Confidentiality Clauses are still permissible (subject to state law), but it is wise to assess those employees who are currently only subject to non-competes (under the assumption they could not use privileged information if they could not work) and convince them to sign NDAs and Confidentiality Clauses instead.

Time is of the essence in this regard, as your goal should be to ensure all your employees – whether executives or non-executives – are adequately covered by an NDA or Confidentiality Clause before the expiration of the four-month effective date – at which time those employees only subject to a noncompete will be free to share your most precious trade secrets with your business rivals and competitors.

Is This the New Status Quo?

The question of the hour in scholarly legal circles is whether the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule will become a standing law prohibiting noncompetes going forward. While loathe to engage in a full constitutional analysis in this short posting, we doubt the Final Rule will remain in effect for too long. We suspect that the U.S. Supreme Court is unlikely to uphold the rule in the face of the extreme impact it will have on individual states’ abilities to regulate trade and business practices within their borders – and this assumes that U.S. Supreme Court will even have an opportunity to address the issue. Because the Final Rule has been promulgated by the FTC (a federal agency currently headed by a panel of five appointees; three Democrats who voted in favor of the Rule and two Republicans who did not), a change in administration, particularly a pro-business individual, would likely appoint new leadership to the FTC, thus leading to a revocation of their own published rule. Therefore, like the hurricanes which so often batter our Gulf coast, the FTC noncompete ban Final Rule may not be here to stay, but it will certainly make waves for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

Noncompete agreements have been on an ever-increasing rise for decades – so much that the FTC itself cites statistics which reflect that almost one in five Americans are subject to a noncompete. The implications which may result from all but approximately .75% of noncompete agreements being automatically voided are immense, and it is incumbent on savvy employers and employees alike to ride the wave and use this change in the status quo to their advantage – or otherwise guard against rogue elements harming their business. The Tough Law Firm is here as a guide and advocate as we navigate these uncharted waters. Please do not hesitate to reach out for a consultation if you desire advice on protecting your business or escaping your noncompete agreement.

Want to do further research on the FTC’s new “Final Rule”? Follow the below link:

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/noncompete-rule.pdf